Annotating morphology and lemmata in Greek texts

Experience has shown that the greatest shock for university students of Ancient Greek in Croatia, even when they had been taught Greek in high school, is encountering sentences and texts that the Greeks have actually written. We have tried to treat this shock by preparing a Greek reader, 60 brief selections of Ancient Greek prose from Herodotus to Plotinus, carefully commented and cued to a standard (though outdated) school grammar; the idea is to read four selections each week during our 15-weeks semester. We are now in the second round of trying out the reader, and so far the approach seems to work. You can see another edition of the texts supported by the Alpheios tools at our Eklogai site.

A team of older students prepared a commentary to selections in the reader – digital, clearly structured, with morphological and lexical annotations. To the XML of tokenized texts they have added the ALDT grammatical codes and lemmata. After their work was reviewed, the texts have been enriched by bibliographic data (we added a bibl section, like this) and aligned to their existing CTS URNs wherever possible (the fact that the Perseus Digital Library implemented CTS URNs helped greatly).

Another version of the commented edition, based on CTS URNs

A simple two-part digital publication demonstrates our knowledge of Greek grammar and lexicon, as digitally encoded in the collection.

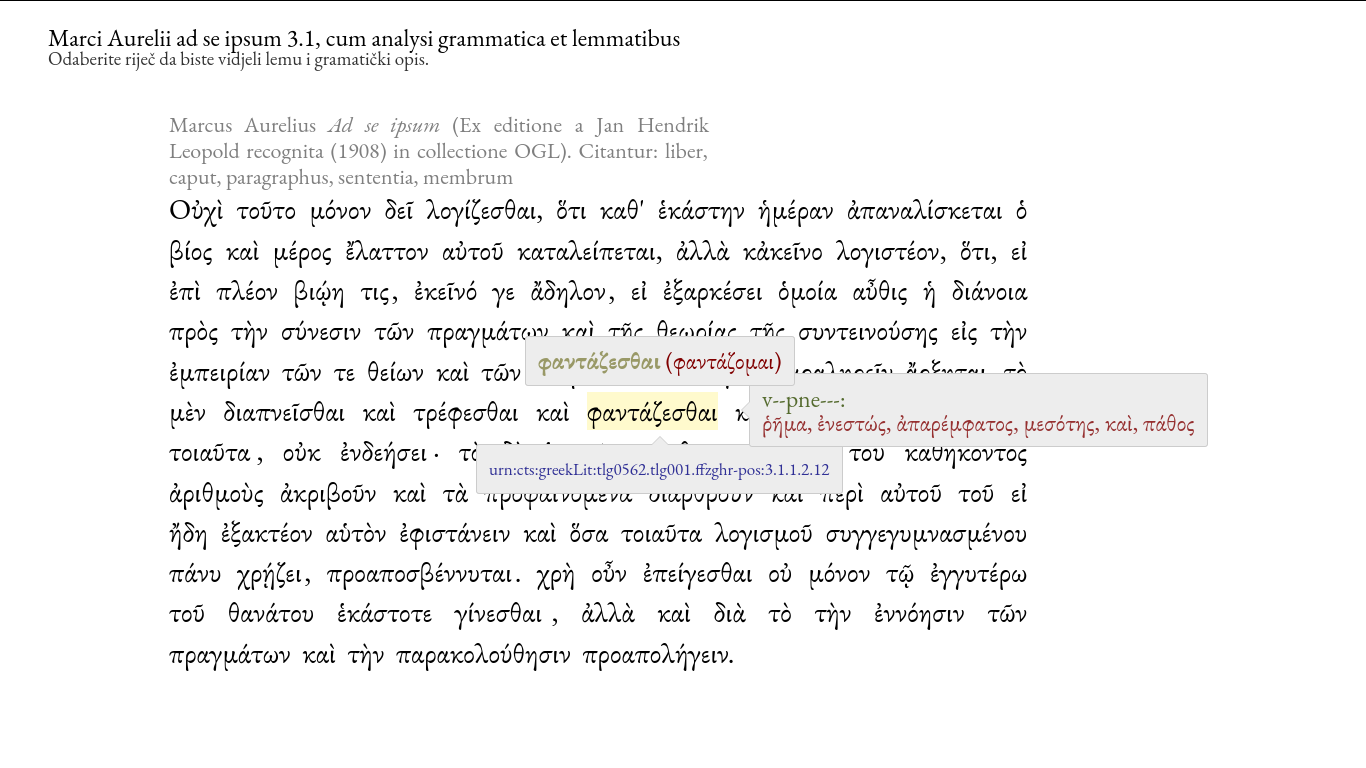

The first part of the publication are texts from the reader with our commentary as (multiple) HTML tooltips, for example Marci Aurelii ad se ipsum 3.1, cum analysi grammatica et lemmatibus. Each word (and punctuation mark) bears three types of notes – a reference to its lemma, a morphological description (in ALDT codes and, in the selection from Marcus Aurelius, in Greek grammatical terms), and a CTS URN which is a live link – see for yourself where it leads to.

A list of all 58 annotated selections from the reader (ordered alphabetically) is here: croala.ffzg.unizg.hr/grcgram.

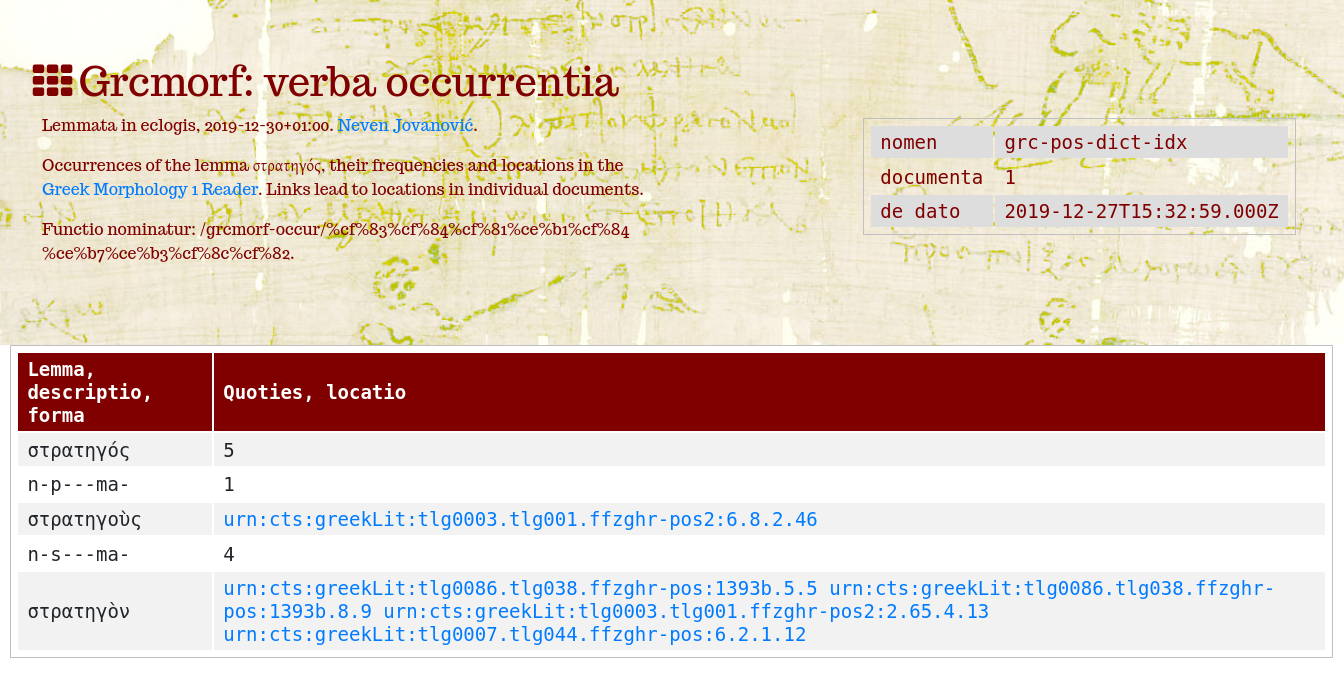

The other part of the publication is a proto-dictionary for our texts. It is a list of all its lemata. The frequency count in that list is a live link as well. It leads to an index entry listing all forms which appear in the reader, their frequency, their morphology codes, and locations at which they occur. Check out the example for the word στρατηγός (you will see that links to locations eventually lead to the same page as the CTS URNs from selections with three sets of annotations, described above).

Technology used and credits

The selections, prepared from CC-licensed texts published by the Open Greek and Latin project and the Perseus Digital Library, have been annotated and reviewed using Perseids and Arethusa.

The repository is on Github: grcka-morfologija (it contains also LaTeX and Markdown sources for other versions of our reader).

The CTS and CITE architecture is developed and described by Neel Smith and Christopher Blackwell at cite-architecture.org and its depositories.

Christopher Blackwell’s wonderful readingKit single-page CEX publications provided a model for displaying annotated texts. The index of forms has been inspired by Syntacticus, a PROIEL project. The Greek grammatical terms are those proposed by William S. Annis on scholiastae.org, Greek grammar in Greek.

The scripts for transforming XML, analyzing CTS URNs, and publishing results as HTML are written in XQuery and served by the BaseX XML database; you will find them in the scripts/xquery and scripts/restxq directories of our repository. For example, a prototype for the Marcus Aurelius selection was produced by this easily generalizable script.

The HTML annotations are being shown by the jQuery plugin Tooltipster.

Last, but under no circumstances the least, the student annotators, μέγα κῦδος ἀράμενοι, were Lovre Katić, Ivona Maleš, Klara Radovniković, Petar Soldo.

What have we learned and where to go next

In the next phase we want to add to our reader a dictionary and, eventually, a set vocabulary exercises. We completely agree with a recent claim that learning vocabulary and vocabulary acquisition are underrated activities in learning historical languages.

The extended exercise of annotating each word in 60 texts got us thinking about three sets of questions we propose below.

Greek literature as L2 texts

Learning Ancient Greek (and Latin, and Biblical Hebrew, etc) is hard in part because the standard levels of foreign language proficiency (A1, A2, B1, B2…) cannot apply here. We learn Ancient Greek in order to read Plato and Aeschylus – imagine learning English for no other reason but to read Shakespeare, Faulkner, and T. S. Eliot.

Certainly, in the vast corpus of Ancient Greek literature there are many passages of simple prose. We have, however, first to have an idea about what is simple (I can tell you that, from the grammar point of view, Aesop’s fables are definitely not simple). Then we have to find the simple passages. Finally, we have to somehow grade or order them – by difficulty for the reader, or by the proficiency level we aim at. All these tasks have never been systematically tackled in Croatia.

Usefulness of lemmata and grammatical annotations for learners

Having designed not one, but three ways of presenting information about lemma and grammar of a word, I am beginning to ask myself how useful this information actually is for a learner. This question calls for experimental research. Would a group with access to our publications be more successful at learning the language, or translating a text, than a group relying on their memory and the dictionary?

Intuition suggests that perhaps a treebank, even one without any labels for word functions in sentences, could be more useful for human understanding than a thorough description of morphology and lexicon (decoding morphology is, by the way, the activity most intensely practised in teaching historical languages today – how did it work for you?).

Ambiguities of grammar and lemmatization

Annotating every last word in a Greek sentence was a challenging enterprise. It was challenging, however, in unexpected places.

The students’ work had to be corrected in points which we either never consider (because they are not important for understanding of the sentence), or which bring to our understanding only very fine shades of meaning: for example, having to decide whether an article, a pronoun, or a participle in genitive or dative is masculine or neuter; having to say whether a “particle” is an adverb or a conjunction.

Some solutions in Arethusa go against the scholarly instinct, such as when an adverb is by default categorized as an adjective (χαλεπῶς as a form of χαλεπός; the adverbs ending in -ον further complicate the issue). Historically, I think, the basis for lemmata in Arethusa was the wordlist of LSJ; there, economically, the adverbs were described under adjectives. Of course, it is possible to create our own lemmata if we’re not satisfied with Arethusa’s defaults; still, the current situation somehow challenges the patience of a grammarian.

Something similar can be said for lemmata. To be able to choose between ἄν1 and ἄν2 (as offered by the lemmatizer in Arethusa) we have to know what is represented by the respective index number (luckily, here we can rely on Logeion or on Christopher Blackwell’s CEX edition of LSJ). In general, lemmatization of Greek is, I believe, a serious issue that requires a robust general solution. There is also a political side to such a solution – it would only work if it is supported by communities influential in classical philology and classical studies in general. But more about that elsewhere.