A textual problem

For an Ancient Greek reader we’re preparing at the University of Zagreb, Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences, I had to typeset a commented passage of Pseudo-Lucian’s Cynicus. The passage (Luc. Cynicus 18.8) was selected by one colleague, the paedagogical commentary was prepared by another. While I was typesetting, a sentence caught my attention. Lucian’s, or Pseudo-Lucian’s, philosopher is telling how the ordinary people are riding a hundred of out-of-control horses of passions and affects, how they are carried in any direction the horses choose, and how they might be thrown from the saddle any minute: “ἴστε δ’ οὐδαμῶς πρὶν πεσεῖν ὅτι πείσεσθαι μέλλετε.”

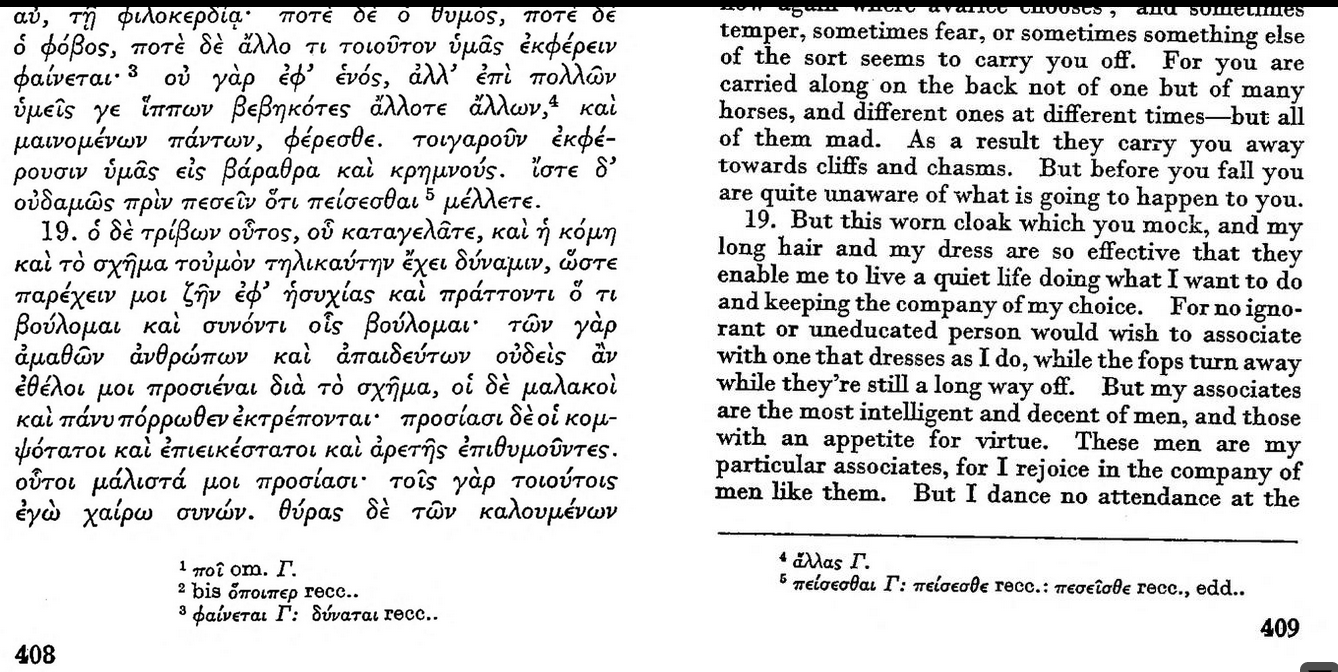

The passage was difficult to understand in its current wording. “And you do not know, before you will fall, that you are about to – what?” πείσεσθαι should be future infinitive from πάσχω, “you are about to suffer” (i. e. a fall); “what is going to happen to you”, says, somewhat coyly, a modern translation. But I wanted to check the text, and its transmission, in other editions; were there any variants in the manuscripts? Did other editors choose something else?

Reaching limits

This checking of lectiones variantes in different editions – one of the basic philological moves, one we all were trained to do almost instinctively – is not easy to do in the digital space. In the first place, I had to find out which edition the Thesaurus linguae Graecae was using (my colleague was working with a TLG text). The TLG’s Cynicus is from the Loeb series edition “Lucian, vol. 8”, Ed. Macleod, M.D. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1967. So a search for other editions was in order.

On the web, we tend to start from a general query: Google or the like, then a large library of digitized bookssuch as archive.org or the Deutsche digitale Bibliothek. This was not very fruitful. The search was complicated by the fact that Lucian’s works are published as multi-volume series, that one has to guess the volume and the location of the Cynicus. Moreover, Googling just some of the words “ἴστε δ’ οὐδαμῶς πρὶν πεσεῖν ὅτι πείσεσθαι μέλλετε” produced surprisingly few results from Lucian, even in Google Books; Plato and Sophocles create a lot of noise for search engines’ algorithms.

On the other hand, Hathi Trust was very useful. It was possible to filter the results of a search there to include just Lucian (I am not sure whether it will be possible to share the search string, though).

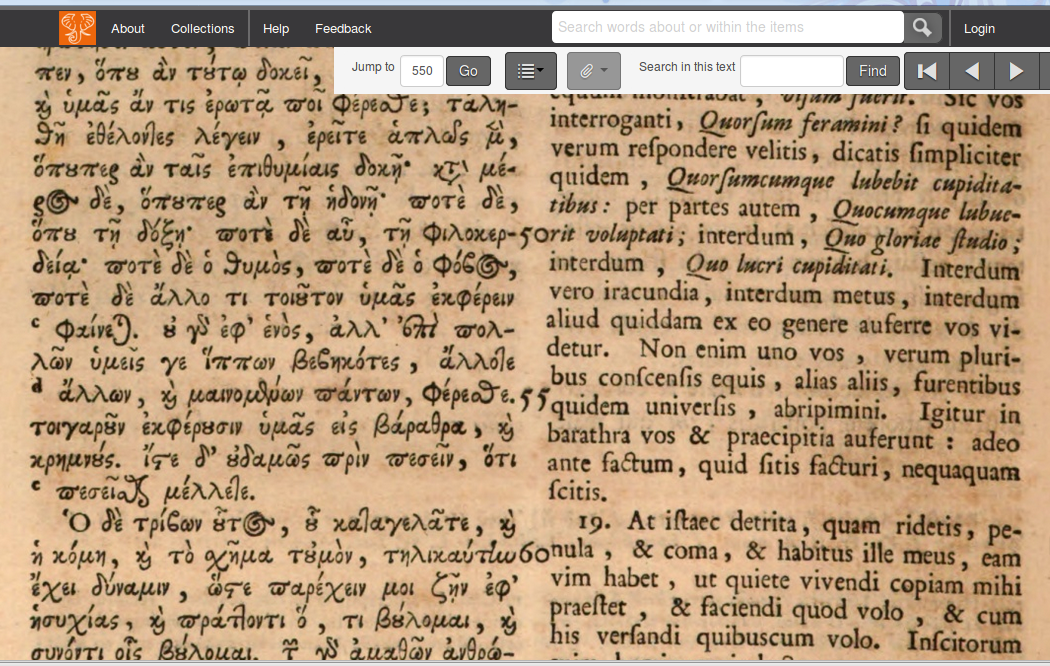

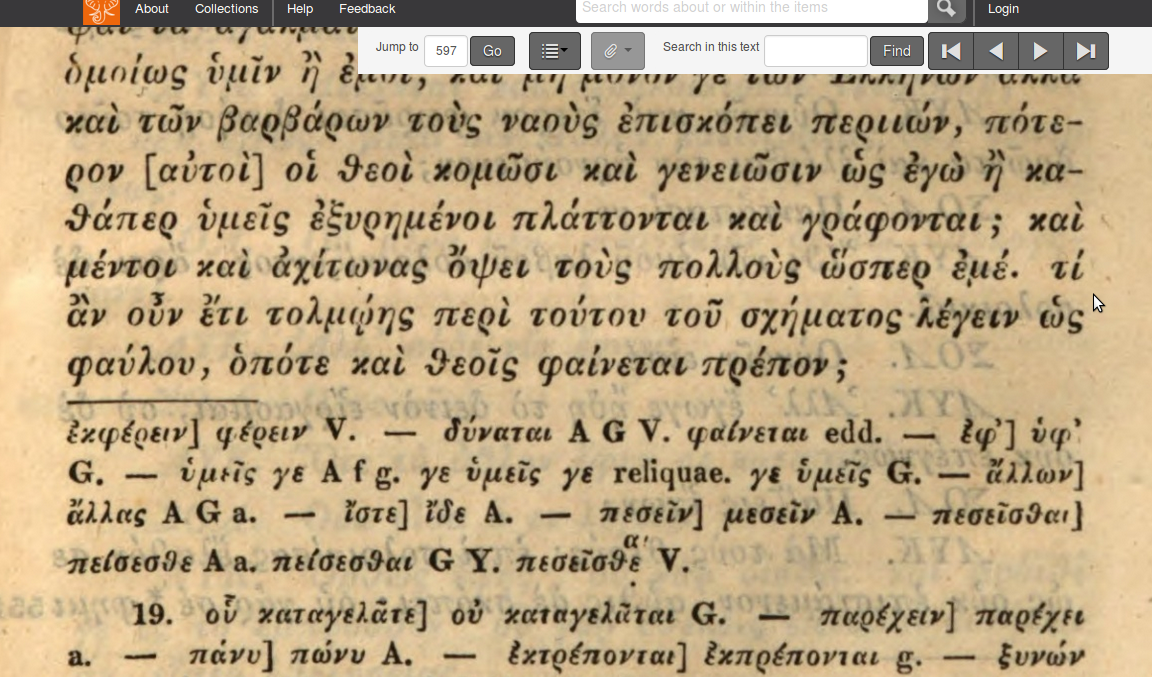

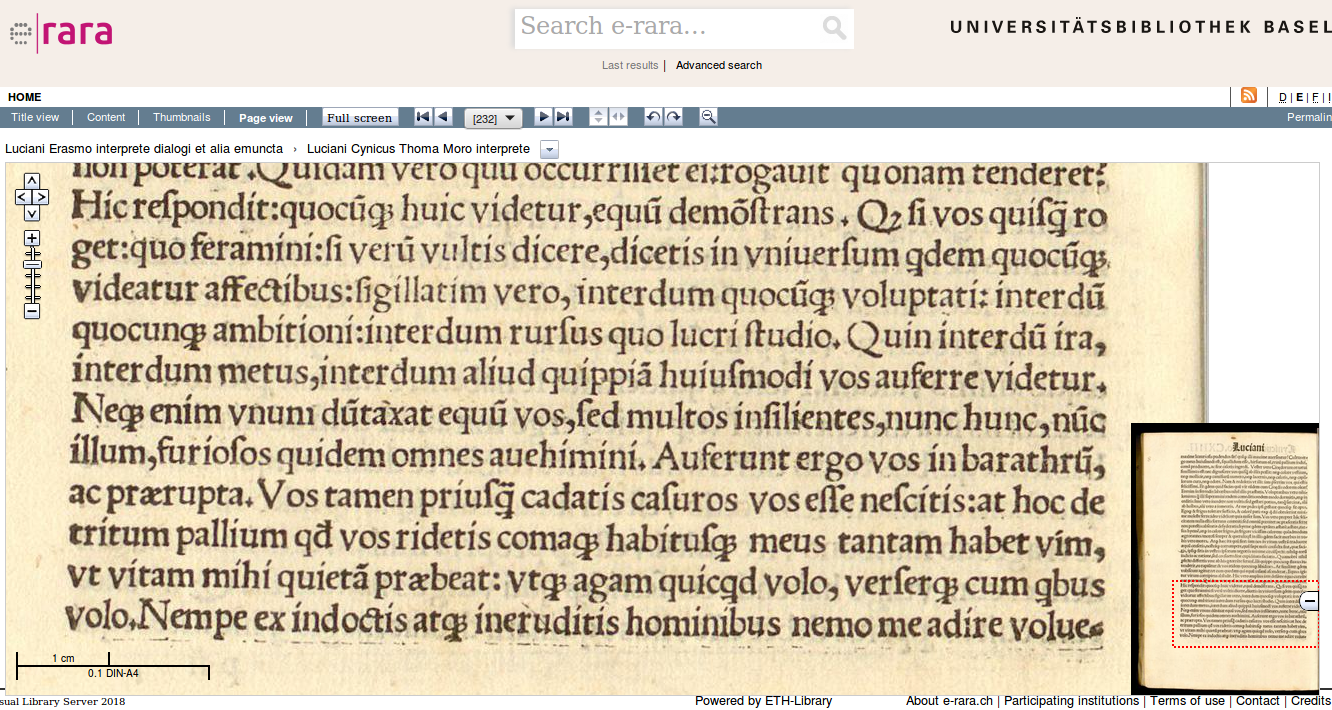

Thanks to Hathi Trust, I’ve learned that the editions of Reitz and Hemsterhuis (1743), Iacobitz (1841), Weise (1847), Bekker (1853), and Dindorf (1858) all read πεσεῖσθαι, not πείσεσθαι. Iacobitz’s is the only of these with an apparatus criticus, and there it can be seen that πεσεῖσθαι is actually not in any of the manuscript families.

This must be the reason why M. D. Macleod, in his 1967 Loeb and also in volume 4 of his Oxford Classical Texts edition from 1987, has chosen to print πείσεσθαι. But, in the brief 1967 apparatus, Macleod writes: “πείσεσθαι Γ: πείσεσθε recc.: πεσεῖσθε recc., edd.” He remains quiet on the rich and influential tradition – present not only in 19th century editions, but in Latin translations as well – of reading πεσεῖσθαι. The latter reading has, to be honest, certain stylistic value, as part of a figura etymologica, and I find it more effective.

I cannot tell at the moment what reasons Macleod gave for printing πείσεσθαι in his 1987 OCT apparatus. This edition remains outside the internet, and, besides, the editors usually remain laconic to the extreme in the apparatus (a philologist worth his salt should understand the editor’s reasons without any additional explanation, suggests the unspoken ethos of the profession).

Nesselrath’s review of Macleod’s fourth volume of Lucian, Gnomon 62:6 (1990), 498-511, concluded, in general, that Macleod’s edition is valuable because it is “the first complete edition which is critical in the modern sense”, but that the editor has “taken too little account of the 19th century editions”, although “the older philologists could have solved, or helped to solve, many difficult readings” (Nesselrath gives four tightly typeset pages of such readings, though our passage from the Cynicus is not among them).

One more important note. According to the valuable Perseus Catalog, there is no open source (that is, not only freely accessible, but also free to legally reuse for different purposes) digital edition of Lucian’s Cynicus.

Some implications

From the vast beach of Lucian I have picked – or stumbled upon – one particular pebble. How important is it in the grand scheme of things, of the whole Cynicus, of the whole Lucian (and Pseudo-Lucian), of the whole ancient Greek literature? A pebble on the beach. This pebble signals, however, how several generations of scholars – who often, I’m afraid, had more Greek and better grasp on Greek literature than we do, though their tools were technologically backward compared to ours – get forgotten, not once, but twice over. The first time when most of the 19th century philologists and their readings were left out from the modern, 1960s edition. The second time when the 1960s edition became, for all practical purposes, the vulgate of the 20th and, even more, the 21th century. All decent philologists have subscription, or some other form of access to, the Thesaurus linguae Graecae; with that access, they don’t need anything else.

There is another set of issues too. It took me a whole day (and over two decades of internet experience) to find and compare a passage from Pseudo-Lucian’s cynicus in digital facsimiles of 18th, 19th and 20th century printed editions, and to study reviews of some modern editions. I did not have to leave my house, and a lot of wonderful resources came to my rescue: JSTOR, Google Books, Hathi Trust, Deutsche digitale Bibliothek, Lucian’s Online Books Page. But the whole process was extremely painful to document, and I had to document it in a very non-standard, non-replicable way.

And I found out that, I repeat, there is no open source digital edition of Pseudo-Lucian’s texts.

Digital philology (of ancient Greek) needs two things at the moment. It needs an edition of Pseudo-Lucian, that is clear. But it also needs a way to preserve knowledge, and achievements, of past philological generations. To preserve it and to learn from it. Even when we disagree.